THIS DAWN — Africa’s richest businessman, Alhaji Aliko Dangote, drew the first blood, accusing the Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), Engr. Farouk Ahmed, of corruption during a press conference.

Alhaji Dangote quickly drew the second blood against Alhaji Ahmed via a petition to the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) requesting a formal investigation of the latter.

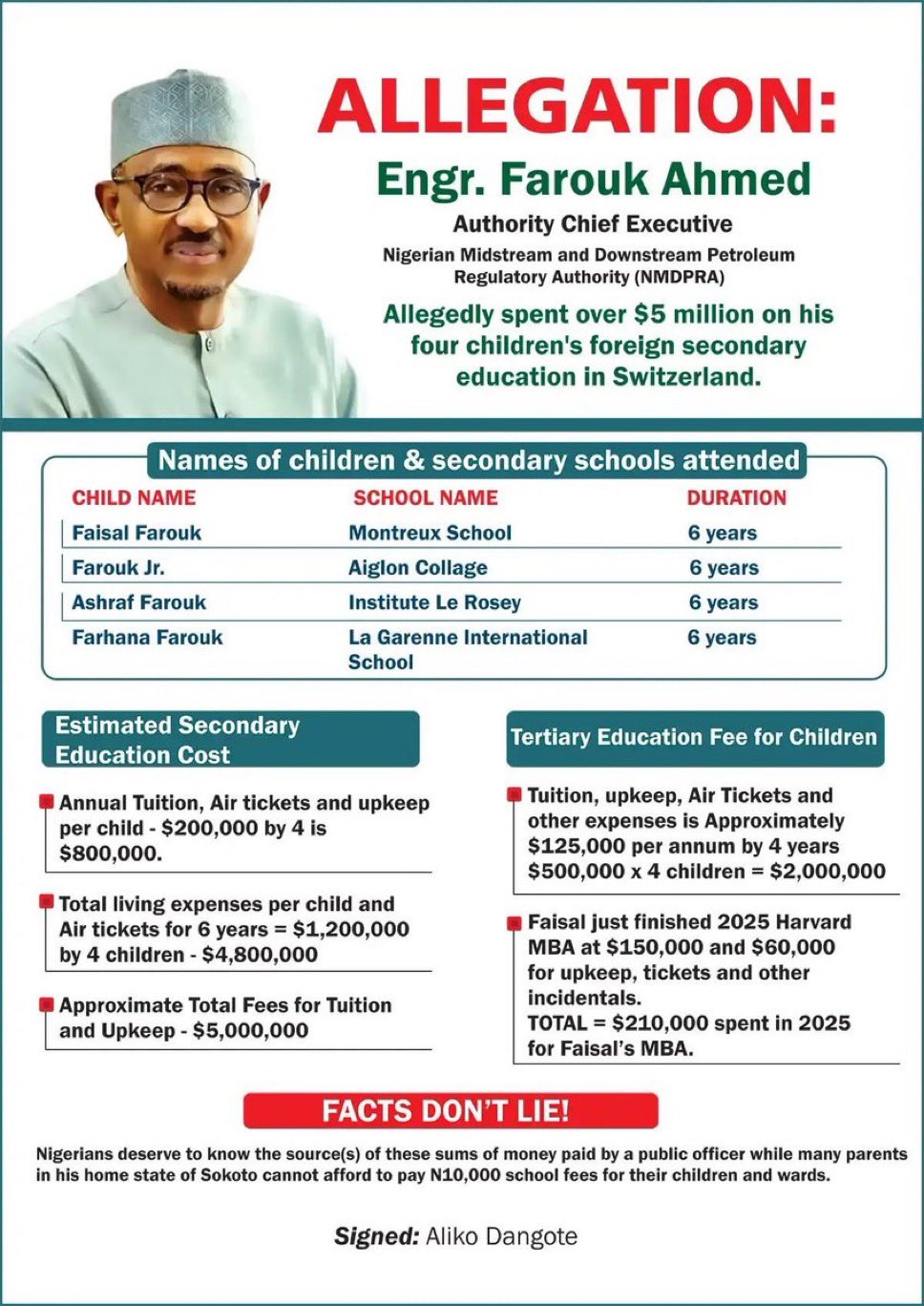

On December 16, Dangote filed a petition with Nigeria’s ICPC against Ahmed, claiming Ahmed spent over $7 million on Swiss boarding schools like Aiglon College and Institut Le Rosey for his four children, including a Harvard MBA.

Dangote printed out the names and school of Engr. Ahmed’s children as shown below as proof of evidence:

Dangote argues such expenses point to diverted public funds, amid ongoing disputes over his refinery’s operations and fuel quality.

The confirmation by ICPC that it has received the formal petition from Dangote against Ahmed is more than a routine procedural disclosure.

It is a moment that tests the credibility, independence, and institutional maturity of Nigeria’s anti-corruption framework.

At face value, the ICPC’s media release of Tuesday, 16 December 2025, is spare and restrained.

It merely acknowledges receipt of a petition and affirms that it will be investigated.

Yet beneath that economy of words lies a complex intersection of power, regulation, corporate influence, and public trust.

Ahmed grandstands

On his part, Ahmed has denied the claims, citing scholarships and savings.

He also welcomed the ICPC investigation to clear his name, while the commission has confirmed it will probe the matter.

The Weight of the Petitioner and the Power of the Office

The significance of the petitioner cannot be ignored as Aliko Dangote is not merely a private citizen.

He is a dominant force in Nigeria’s industrial economy, with interests spanning cement, sugar, fertiliser, and petroleum refining through the Dangote Refinery.

His commercial footprint intersects directly with regulatory authorities such as the NMDPRA, whose mandate governs the midstream and downstream petroleum sector.

Any dispute between such a corporate titan and a senior regulator inevitably raises broader questions about regulatory fairness, institutional independence, and the balance of power between the state and private capital.

Equally important is the position of the respondent.

The CEO of the NMDPRA heads an institution created under the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), a reform framework designed to replace opaque discretion with transparent, rules-based regulation.

Allegations against the leadership of such an authority strike at the heart of the credibility of the PIA itself.

Transparency Begins with Acknowledgement

The ICPC’s decision to publicly confirm receipt of the petition is therefore significant.

In a political climate often characterised by secrecy, leaks, and trial by social media, early institutional clarity matters.

By asserting control of the narrative and affirming due process, the Commission has taken a necessary first step toward maintaining public confidence.

However, transparency cannot end with acknowledgment. It must extend to the manner, depth, and independence of the investigation that follows.

The Real Test: Independence and Due Process

Nigeria’s anti-corruption agencies operate under intense public scrutiny, shaped by past cases that appeared selective, politicised, or quietly abandoned.

Where powerful interests are involved, scepticism deepens.

The ICPC must therefore ensure that this investigation is insulated from political influence, corporate pressure, and public hysteria.

Its credibility will depend not on who is involved, but on how the process is conducted and concluded.

Clear procedures, professional restraint, and a demonstrable commitment to the rule of law will be essential if the Commission is to avoid reinforcing public cynicism.

Petitioning Versus Weaponisation of Institutions

This case also highlights a delicate structural tension: the difference between legitimate petitioning and the potential weaponisation of anti-corruption mechanisms.

Every citizen has the right to petition law enforcement agencies, regardless of wealth or status. That right must be protected.

At the same time, when the petitioner wields enormous economic power, institutions must be especially vigilant to ensure that regulatory disagreements are not reframed as criminal allegations for strategic leverage.

Conversely, shielding public officials from scrutiny simply because of their office would be equally corrosive. Accountability loses meaning when power confers immunity.

Why the Petroleum Sector Raises the Stakes

The sensitivity of this case is amplified by the sector involved.

Nigeria’s petroleum industry has historically been a hotbed of corruption, regulatory capture, and revenue loss.

The Petroleum Industry Act was meant to change that narrative.

Any allegation touching the leadership of a key regulator must therefore be examined not only for individual culpability but for what it reveals about institutional safeguards, governance structures, and systemic resilience.

The ICPC must strike a careful balance.

A rushed investigation risks error and politicisation; a prolonged or opaque process risks suspicion and conspiracy.

Timely, lawful updates and a clear, evidence-based outcome—whether exoneration or prosecution—are essential to sustaining trust.

Presumption of Innocence and Public Responsibility

Finally, it must be stressed that a petition is not a verdict.

Nigeria’s public discourse too often converts allegations into conclusions.

Due process exists to protect the innocent, discipline the guilty, and preserve institutional legitimacy.

This episode is ultimately a test of systems, not personalities.

If the ICPC conducts its investigation with professionalism and independence, it will strengthen public confidence in Nigeria’s anti-corruption architecture and regulatory reforms.

If it falters, the damage will extend far beyond this case.

The Commission’s brief statement has opened a chapter.

How it closes will speak volumes about the state of governance and accountability in Nigeria.